Fulbright in Ukraine

In 2016 Yuri Yanchyshyn was awarded Fulbright Specialist Status, and in the spring of 2018, under the auspices of the Fulbright Program, spent six weeks teaching in Lviv, Ukraine. The following introduction, images, and personal impressions describe his experiences.

INTRODUCTION

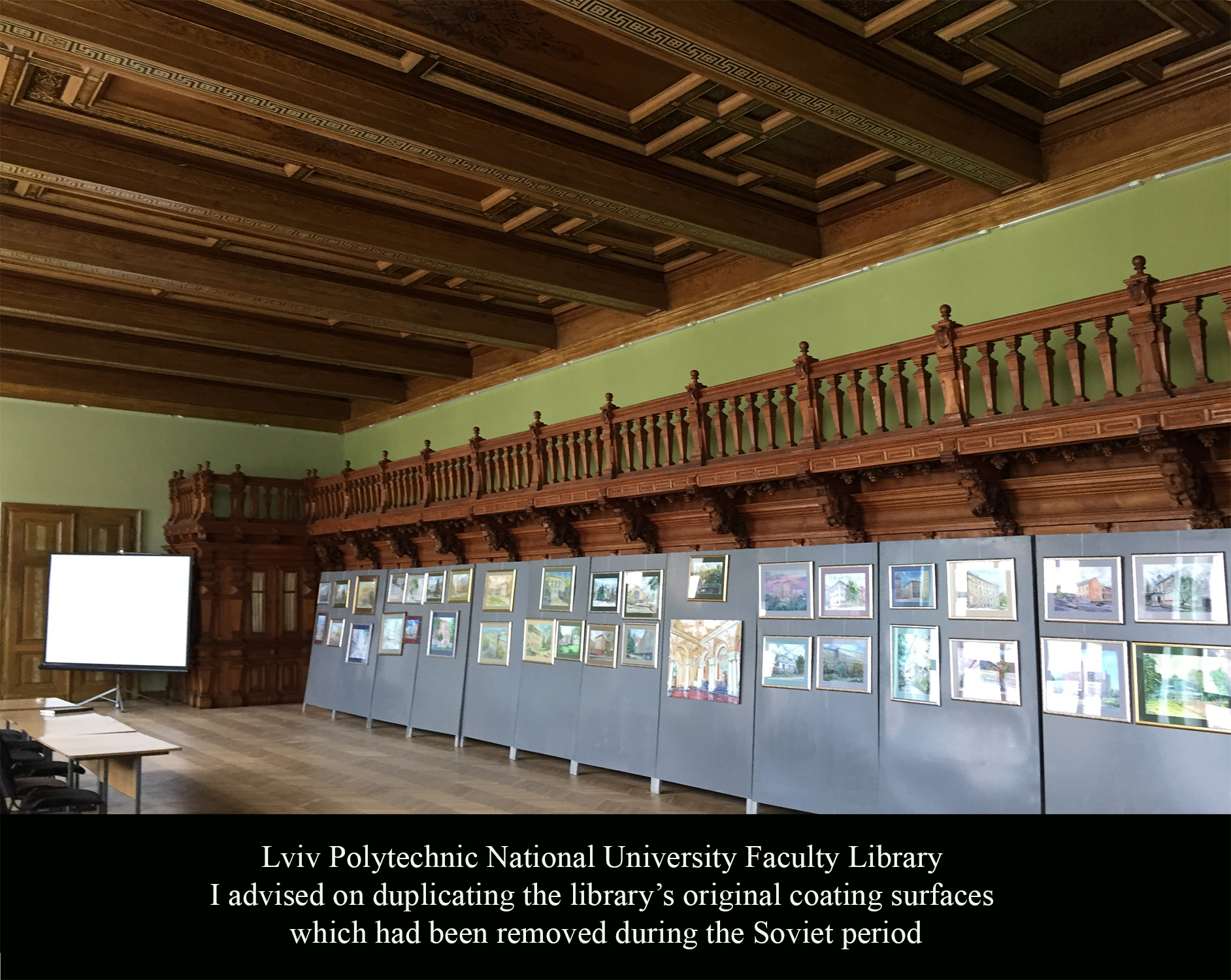

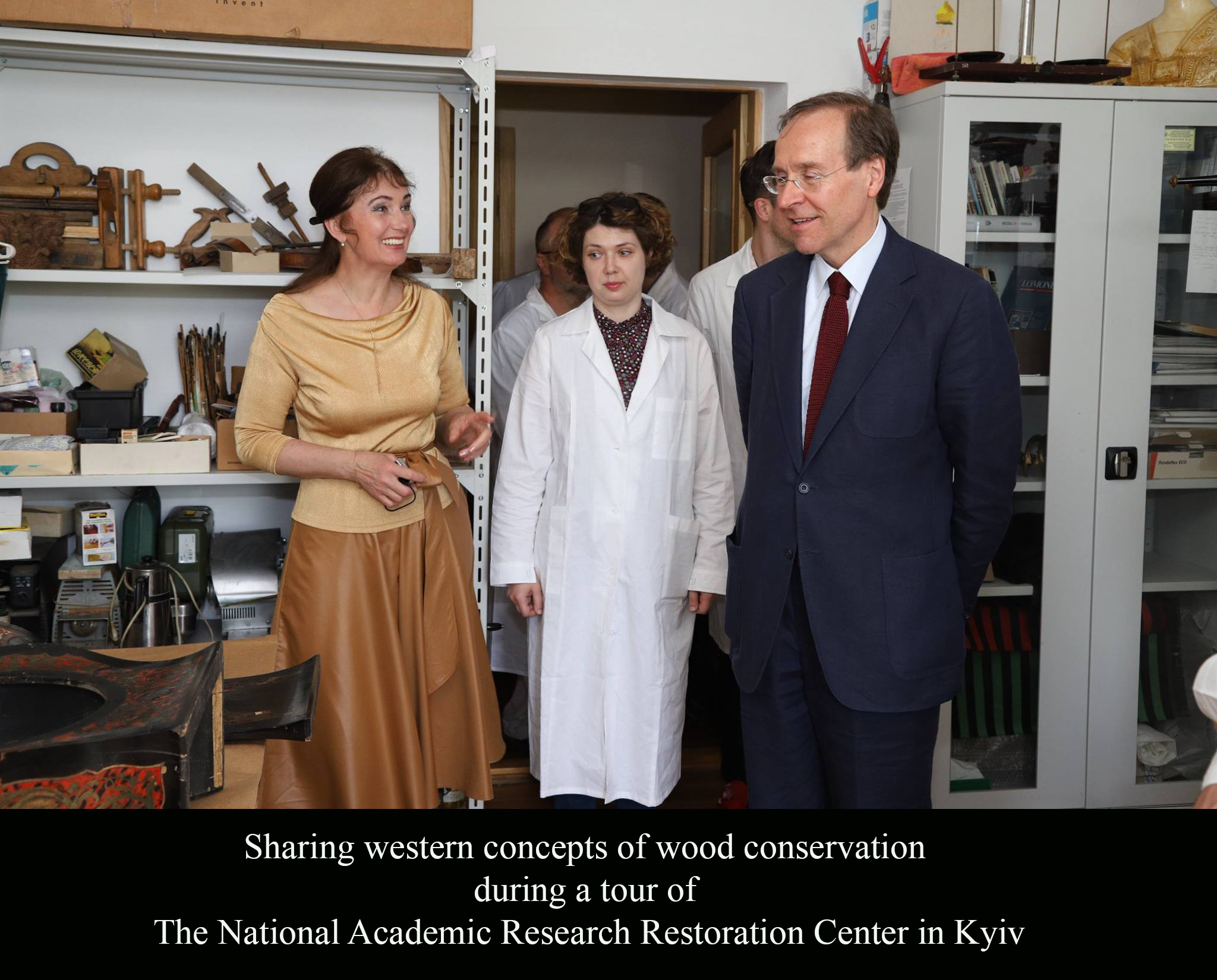

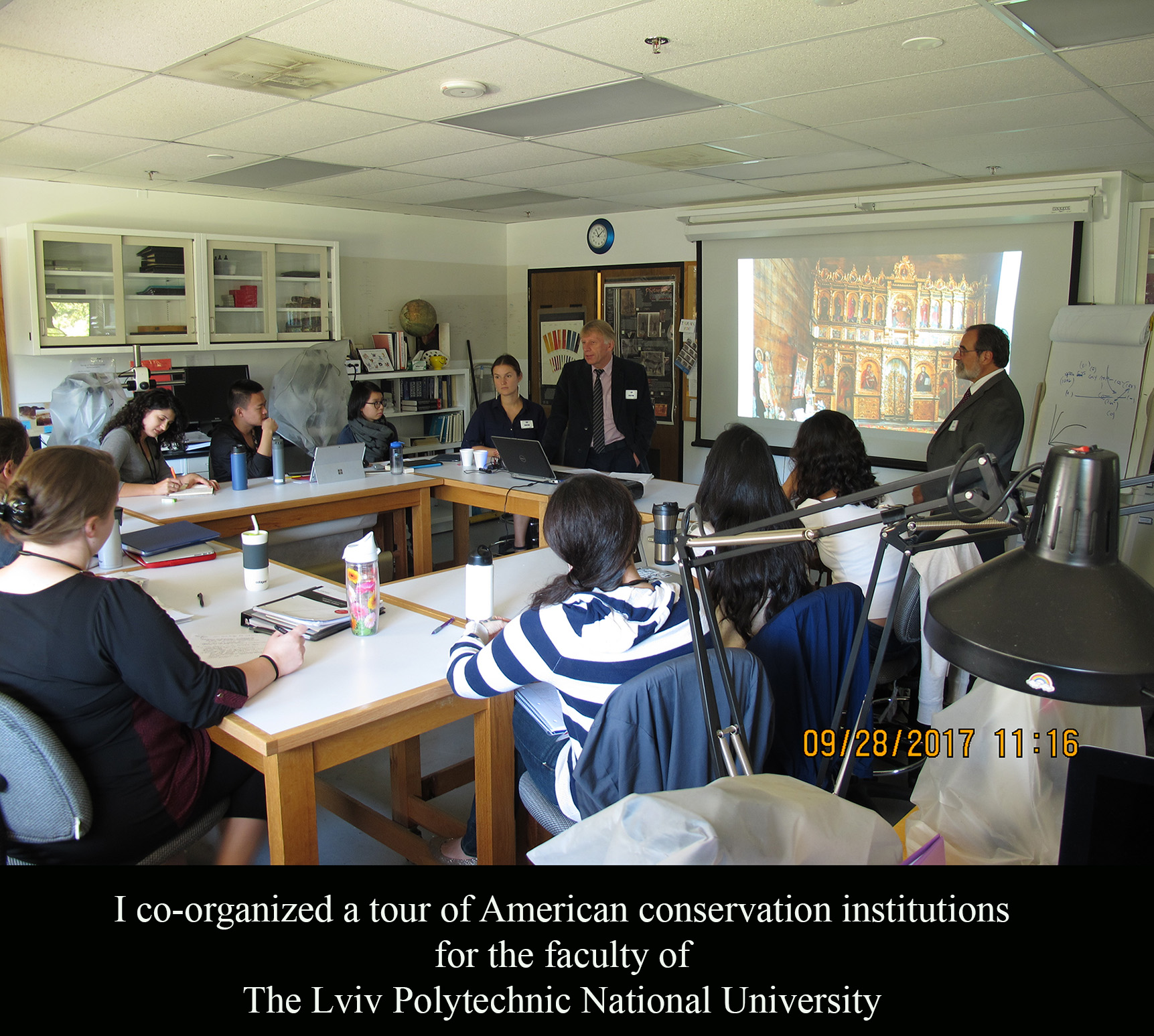

At the invitation of Professor Mykola Bevz Ph.D., Head of the Department of Architecture and Conservation, Lviv Polytechnic National University in Lviv, Ukraine, I spent six weeks introducing the department’s students to the fundamentals, strategies, and techniques of wooden object conservation. Professor Bevz wanted to expand his department’s program, then limited to stone conservation, to include wooden objects as well. The goal was to educate his students utilizing a Western model, so that they would be able to preserve Ukraine’s UNESCO World Heritage Site wooden churches, its many polychrome sculptures, icons, furniture and other wooden artifacts for generations to come. Realizing that the expertise for this undertaking was lacking in Ukraine, he extended an invitation, and my first ever journey to the homeland of my parents began. In addition to teaching, the following images highlight other areas of my activities, such as advising on treatment options, advocating for the conservation of Ukraine’s cultural heritage and upgrading its conservation education programs.

TREATMENT ADVISORY

ADVOCACY FOR CONSERVATION

AND

CONSERVATION EDUCATION

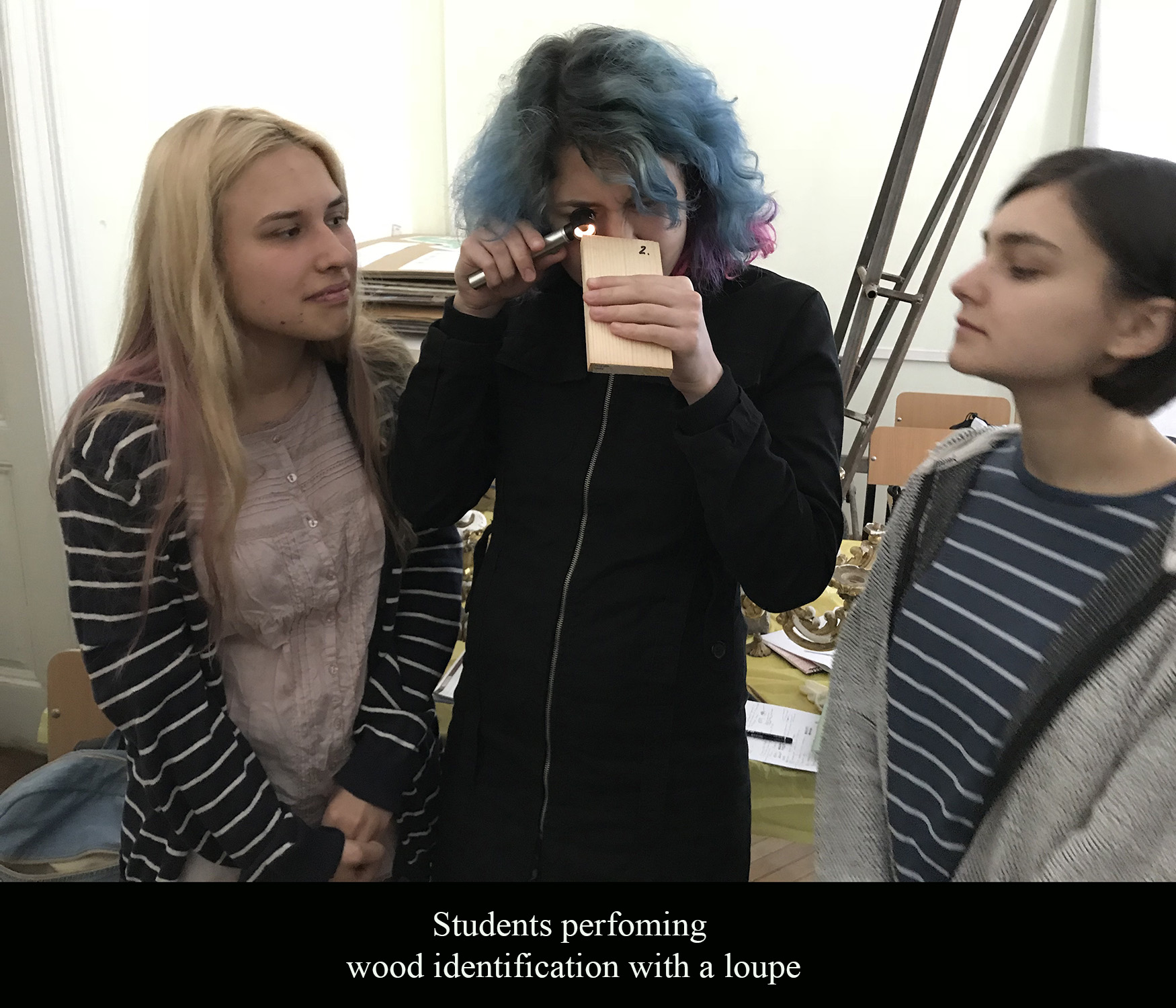

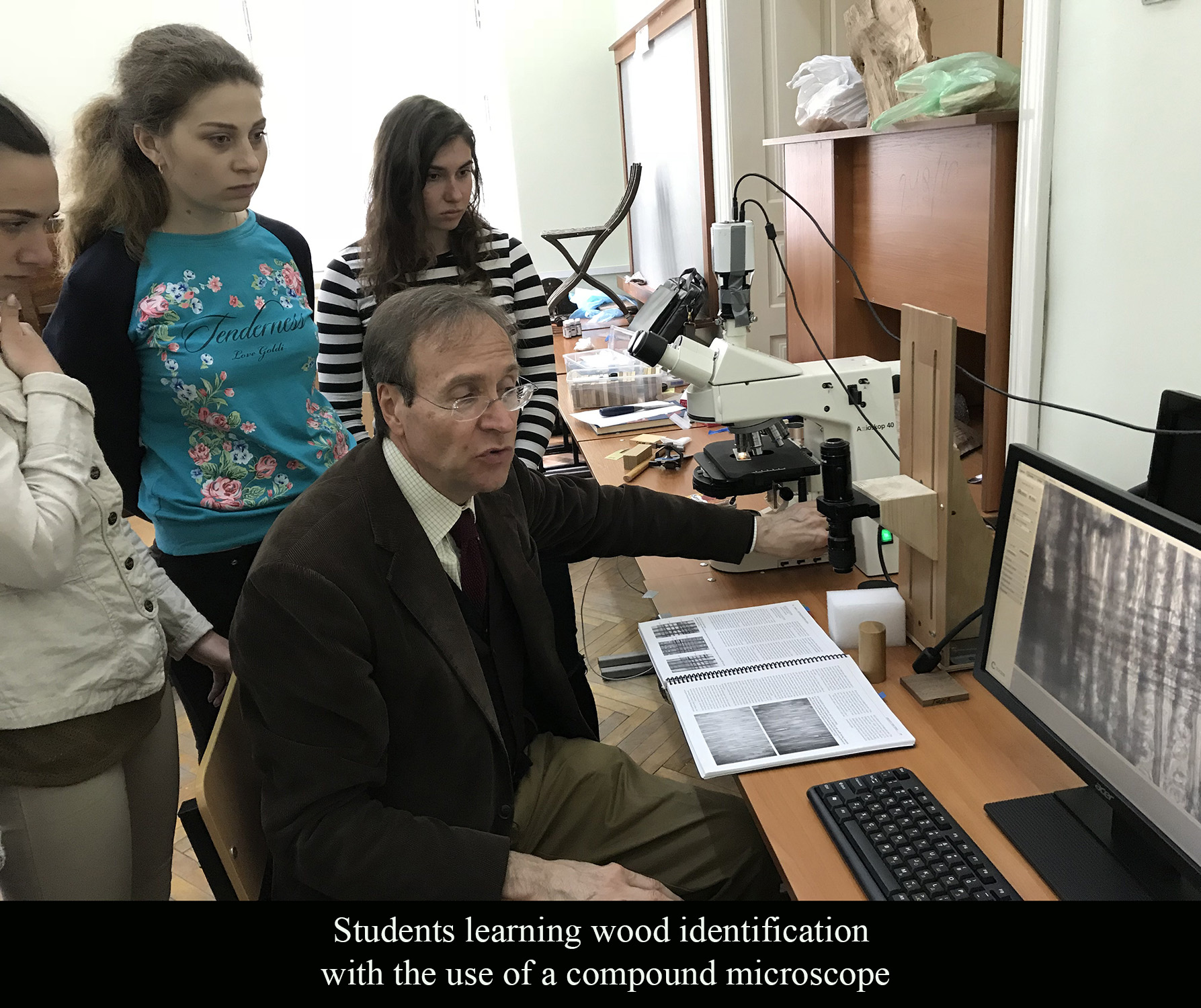

LECTURES AND PRACTICAL EXERCISES

PERSONAL IMPRESSIONS

The strongest impressions of my Ukrainian Fulbright experience were created when I would come across an art treasure, hidden away, or even in plain sight, ostensibly unrecognized, but nearly always in a poor state. These discoveries became an almost a daily occurrence, uncovering the old, which would transform into the new.

My discoveries were not only the art objects, but also the individuals who cared for them, and the young students who would learn how to preserve these objects for the future. Being able to converse fluently in Ukrainian was an asset during my journey, especially in interacting with my students. Even though many had only modest English language skills, they made up for it with their enthusiasm. During our conservation vocabulary practice sessions in front of works of art, they would jump in with questions about life in New York and the world of conservation beyond Ukraine’s borders.

It was also a remarkable experience to meet individuals who genuinely cared about their culture, such as the faculty of Professor Bevz’s department, and many others, who worked tirelessly to preserve it. Earlier, in 2014, a test of that caring occurred with the Revolution of Dignity, where ordinary citizens made a commitment to the West. They decided to re-define themselves, embarked on a process of re-examining Ukraine’s history, re-assessing its cultural heritage, and how best to preserve it. That was the reason I was invited to assist.

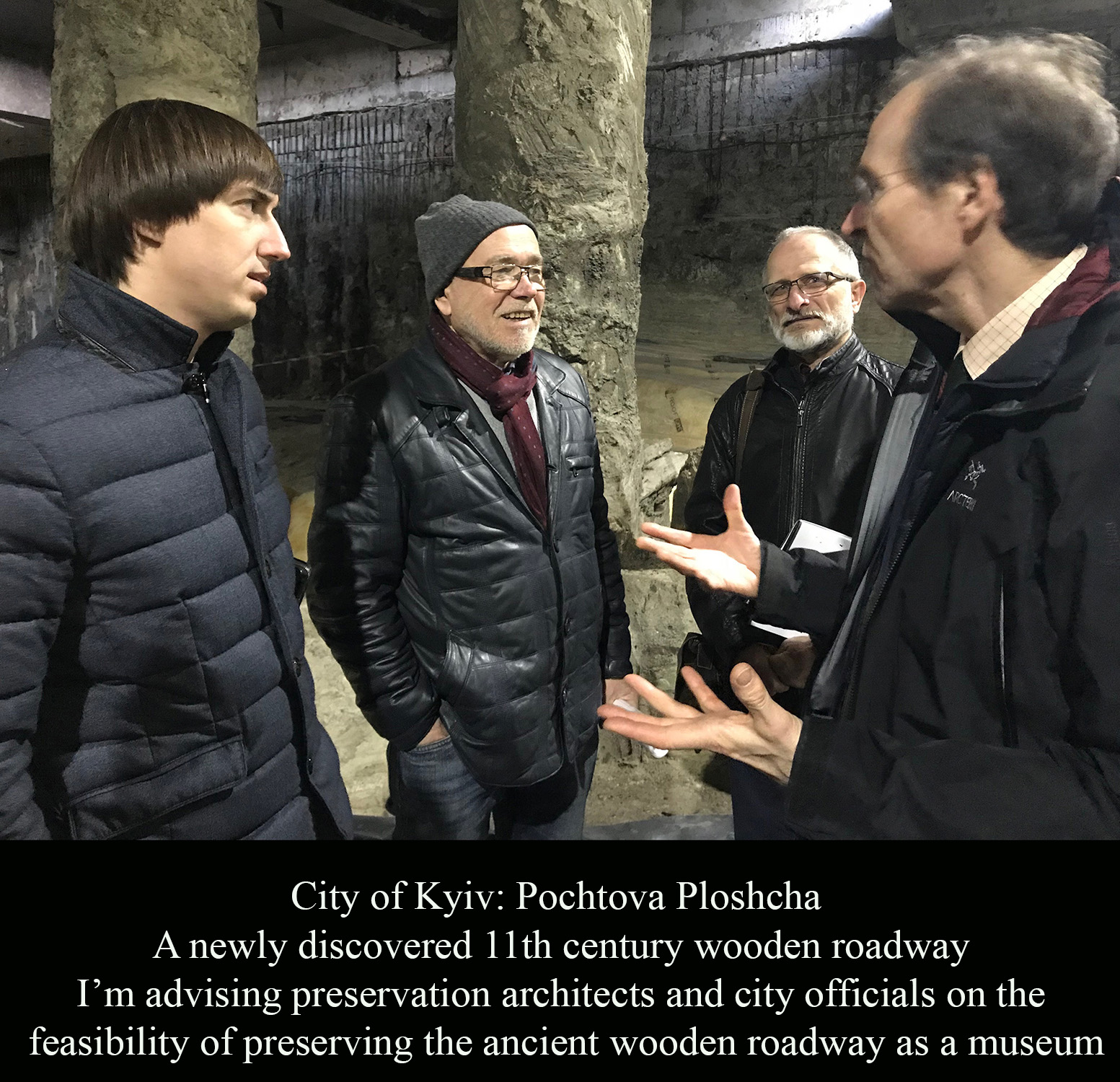

In fact, during my visit, the Ukrainian Parliament held its first ever hearings on historic preservation, at which I spoke ( photo above). The recent discovery of an 11th-century wooden roadway in the capital city Kyiv (photo above), has led to fresh insights into its medieval history. And although I had heard of Ukrainian wooden churches in my childhood, I was unprepared for the experience of seeing them in person. Visiting these churches, as well as viewing the thousands of icons, paintings on canvas, furniture, and wooden objects made me realize that this little-known history needs to be conserved and illuminated.

It’s a massive undertaking, one for a whole generation of new young conservators. Will they be sufficiently prepared? Although I witnessed many examples of excellent hand and eye skills, I saw very few microscopes. I then understood that the science aspect of their education required strengthening. So I spoke up and lobbied for more chemistry in their curricula. I co-organized a tour of the USA conservation institutions. And when I learned that their department was creating a conservation lab, I donated the microscope I had brought with me. A small gesture to get them on the right path.

I consider myself privileged to have helped them along their way.

For 75 years, the Fulbright Program has given hundreds of thousands of passionate and accomplished students, scholars, artists, and professionals of all backgrounds and fields the opportunity to study, teach and conduct research, exchange ideas, and contribute to finding solutions to complex global challenges. To mark the celebration of this momentous occasion, program alumni shared their vision and their Fulbright experiences with us.

Fulbright U.S. Specialist 2016 and Scholar 2018-2019 in Ukraine Yuri Yanchyshyn is the Principal and Senior Conservator of two firms in the New York City metropolitan area, Period Furniture Conservation LLC and Kensington Preservation LLC.

Yuri Yanchyshyn worked with wooden objects and their owners for over 30 years in a variety of settings, from a cabinet-maker’s shop to the laboratories of The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Private collectors, museums, architects, decorative arts historians, fine arts advisors, designers and other conservators have all entrusted treasured items to Yuri’s care, and institutions such as New York University’s Institute for Fine Arts Conservation Center invite him to lecture.

Yuri holds degrees from the University of Michigan and the California Institute of the Arts. He received advanced training in conservation from the Amsterdam Academy for Restoration and the Smithsonian Center for Materials Research and Education, and frequently participates in ongoing continuing education courses.