It is (Almost) All in the Mind: Guarding Against Furniture Fakes

from Chubb Collectors

By Yuri Yanchyshyn, furniture conservator

February 2015

Seek advice from outside experts before you purchase.

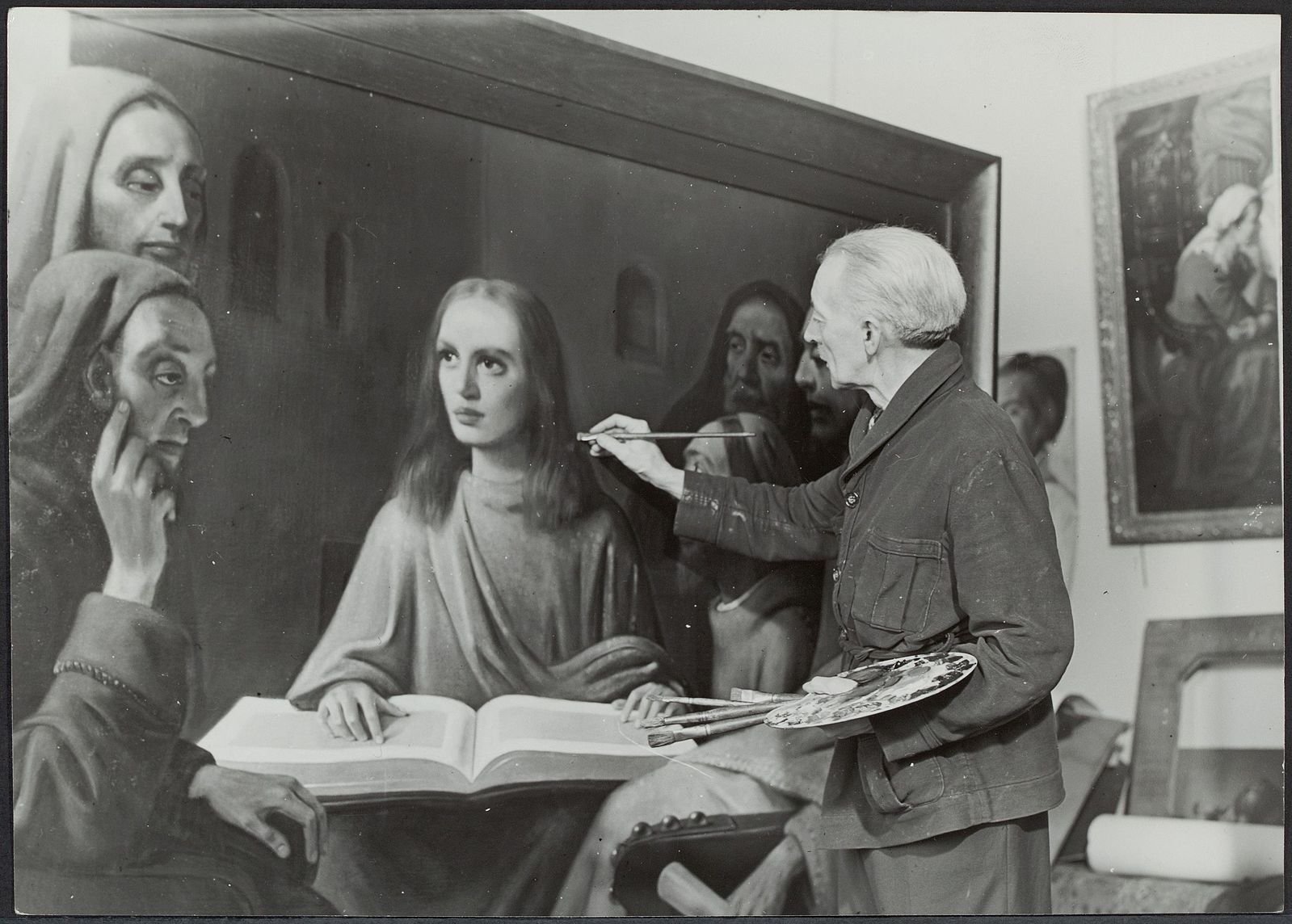

Hans van Meegeren, painting in 1945 to show he forged Vermeer paintings. Photo: commons.wikimedia.org.

There have been copies sold for as long as human beings have valued particular types of objects. During the Roman Republican period and early Empire, there was a robust trade in copies of Greek statuary. Many of these copies were openly acknowledged as such, while others were deliberately intended to deceive.

Then there was the medieval relic trade, which prompted 16th-century religious reformer John Calvin to note that if all the purported relics were brought together in one place, "it would be made manifest that every Apostle has more than four bodies, and every Saint two or three." This trend has continued right through the present day. In recent years, fakery in “high art,” such as painting, tends to be particularly well documented. Certainly from the mid-20th century onward, there have been numerous high-profile fakers of paintings, including 19th-century Dutch painter Hans van Meegheren, 20th-century German artist Wolfgang Beltracchi and, most recently, American painter Mark Landis.

Like other valued objects, furniture is not immune from copying or fakery. Nearly everyone has heard some variation of the quip that there are more extant 16th-century English oak refectory tables than there were dining rooms in all of 16th-century England! Modern scientific methods and broader access to detailed information about period materials and techniques have made it possible to more readily identify things that are not quite what they are represented to be. There are identified fakes among the extraordinary American collection at Milwaukee’s Chipstone Foundation, proudly displayed for educational purposes. And there is the famous “Brewster Chair” in The Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Mich., originally purchased as a Mayflower-era original but later shown to be a fabricated 20th-century replica. There are also reports in the news of the collaboration of British furniture restorer Dennis Buggins and high-profile British antiques dealer John Hobbs on items sold as fine, 18th-century European furniture.

Understanding the psychology of fakery

By its very nature, deception involves psychology. There is first the mindset of the forger, a painter or craftsman who intends to pass an object off as something it is not. Typically these people are working from one of two motives. The first—and likely less common—is bravado. The creator of the “Brewster Chair,” American sculptor Armand LaMontagne, undertook his project in 1970 after a contentious exchange with a curator at The Wadsworth Antheneum. Scientific examination techniques would not become widely accepted and available until the late 1970s and early 1980s, and in those pre-scientific days LaMontagne wanted to—and did—prove that he could fool the so-called experts. Similarly, from the late 1980s until quite recently, American Mark Landis expressed satisfaction in the creation and donation of “neo-Impressionist” works to unsuspecting collections.

While neither of these forgers attempted to profit from their work, the driving force for some fakers is financial gain. Wolfgang Beltracchi realized substantial returns on his handiwork over several decades. Money was at the heart of the allegations regarding the Hobbs/Buggins collaboration; Hobbs was known for his exclusive clientele and commensurate price tags. And no doubt the anonymous craftsmen who created the counterfeit items in the Chipstone Collection, or the individuals who marketed them, would not have done so without significant market demand for these items.

It is thus relatively easy to understand why people may want to fool other people. But to achieve success, the marketers of fakes must have access to people who are willing to be deceived. Without that, fakery of antiques and fine art objects would not be successful. What an object is “represented as” means something to the buyer or recipient—usually something that goes well beyond the object itself. In the case of the curatorial staff who acquired the Brewster Chair in 1970, due diligence was not as common as it is today. It was the advent of thorough scientific examination, which occurred after the chair’s acquisition, that would prove the forgery.

Knowing when to be suspicious

For the faker to triumph, the story he is telling must be believed. In theater, the audience “suspends disbelief”—allowing something that is improbable to be real for a time in order for the story to work. When considering the purchase of rare or antique furniture or other art objects, the buyer is perhaps well served to employ suspension of belief rather than disbelief—to consider very thoroughly that maybe the object is not what the seller is saying it is. There are at least three red flags that should prompt further investigation before a financial commitment is made:

Items from the period are fashionable. Since making money is the aim—and forgery is often a painstaking endeavor—forgers will typically focus on periods that are in demand. We have seen this with 17th-century to 19th-century American furniture (Brewster Chair, Chipstone Collection), possibly with 18th-century European furniture (the Hobbs/Buggins fakes) and more recently with a panoply of objects from China, notably ceramic ware.

Desire for a particular feature or specific object is high. The more desirable or unusual a particular feature or object is, the greater the forger’s motivation. By his own account, Beltracchi’s career in forgery began when he noticed that 17th- and 18th-century Dutch winterscapes sold at higher prices when they included skaters, so he started by adding skaters to genuine old paintings and gradually went on to create his own “17th-century” skating scenes. In the Chipstone Collection, many of the items deemed to be fake are candle stands; apparently this type of object was especially appealing to collectors in the 1930s.

Provenance is either cloudy or suspiciously appealing. Everyone loves the story of the dusty canvas from grandma’s attic that turns out to be a masterpiece, or the neglected side table that proves to be a genuine Hepplewhite (Roald Dahl’s short story, “Parson’s Pleasure,” has an ironic take on this), but skepticism about great objects that appear out of nowhere is warranted; the sudden appearance of the Brewster Chair on the Maine porch of one of Armand LaMontagne’s friends might well have aroused suspicion. Similarly, a provenance that is unbelievably good—but minimally documented—should raise eyebrows. Beltracchi created an elaborate backstory for many of his forgeries involving a Jewish collector in pre-WWII Berlin and included inventory labels. This was a story that should have been more fully verified.

Protecting your investment

There are a few things you can do to protect yourself from unscrupulous sellers (or the unscrupulous people who sold them the objects in the first place) and to corroborate or disprove the stories they are telling. The first is to insist on a detailed provenance for any significant item you intend to purchase. This should include records that go beyond the dealer’s notes. Keep in mind, though, that skilled forgers can possibly forge these, too, so they will need to withstand careful scrutiny and third-party corroboration.

Another thing you may want to consider, especially when the financial stakes are high, is engaging an outside team of experts to examine the objects and offer their views. The most effective teams typically consist of the following members:

The appraiser knows the current market for similar objects, including prices and provenance.

The subject matter expert has intimate familiarity with the history of objects from the period, including prototypes and variations.

The conservator possesses the scientific training and methodologies to perform a detailed examination of condition, materials and construction techniques, which could indicate that an object is not what it seems.

The arts attorney will understand the legal ramifications of acquiring a fake.

These experts—usually working at the appraiser’s or arts attorney’s direction—will work together to assemble the object’s real story.

Creating an “honest” illusion

There are two circumstances under which deception is harmless—and even desirable. The first is when a replica is created, say, to visually match a set of items, with no intention to deceive. The second is found in the work of the conservator, who is tasked with sustaining the structural stability, historical faithfulness and aesthetic appeal of fine arts objects. To achieve this, conservators often use techniques that may deceive the naked eye; however, the conservation is documented in a report that is part of the work’s provenance, is readily detected during scientific examination and most are completely reversible so they are not a permanent passage in the object’s story.

Unless human nature changes dramatically, we can all look forward to a robust trade in fakes and forgeries, so arm yourself by seeking the advice of outside experts, and enjoy the work knowing that it is what it claims to be.

Further reading

The following may be of interest. This list is by no means comprehensive.

Overviews of furniture fakery:

www.perrysclocks.com/aihc/authenticating-fakes-and-frauds-of-period-furniture

www.chubbcollectors.com/Vacnews/index.jsp?form=2&ArticleId=249

Furniture fakes from the Chipstone Collection: www.chipstone.org/html/publications/2002AF/BeckerditeMiller/2002BeckMillerindex.html

Hobbs/Buggins collaboration:

www.nytimes.com/2008/05/22/garden/22hobbs.html?fta=y&_r=0

www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/art/news/the-alisters-antique-shop-and-the-fakes-made-from-wardrobes-2151063.html

Mark Landis story:

www.npr.org/2014/09/27/351738720/art-craft-explores-how-one-forger-duped-more-than-45-museums

Art law authentication issues:

www.artlawfirm.com/art_law_pdf/los_angeles_lawyer.pdf

www.artlawfirm.com/publications.html